Across North America we are seeing more stringent thermal requirements in building codes and designers are responding by increasing the amount of insulation in walls, all in an attempt to increase energy efficiency in buildings. But how effective are these changes on building energy use when we ignore the impacts of 3-dimensional heat flow in transition building components, like exposed concrete slabs, window flashings and un-insulated parapets. What if these building components we neglect have a much greater impact on energy than we realize? And how will that affect the decisions we currently make on the building envelope?

Across North America we are seeing more stringent thermal requirements in building codes and designers are responding by increasing the amount of insulation in walls, all in an attempt to increase energy efficiency in buildings. But how effective are these changes on building energy use when we ignore the impacts of 3-dimensional heat flow in transition building components, like exposed concrete slabs, window flashings and un-insulated parapets. What if these building components we neglect have a much greater impact on energy than we realize? And how will that affect the decisions we currently make on the building envelope?

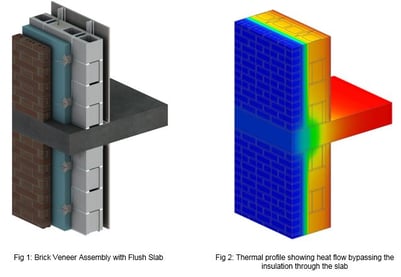

Thermal bridging cannot be completely avoided since many of these transition components, such as shelf angles and canopy penetrations, are required for structural purposes. The building industry has long struggled with how to deal with analyzing these components from a thermal perspective. The current thought process is ‘ if these structural members have to be there, they are small compared to the total wall area AND the energy impacts are difficult to calculate, we can ignore them and focus somewhere else’. This has resulted in codes and standards increasing the thermal resistance requirements of walls and windows (lowering maximum wall U-values), while largely neglecting heat flow between transitional components. More often than not this increase in thermal requirements is interpreted as ‘more insulation in the walls means proportionally better energy efficiency in the building’.

The reality is, we are doing things wrong and as a result, we are making bad decisions. Simply adding more insulation to your walls will not necessarily decrease the energy use of your building if most of the heat flow bypasses the insulation through poor details anyway. This will leave you with diminishing returns as you add more insulation. As an analogy, the building envelope can be thought of as a leaky water bucket with several holes. You may keep trying to plug one spot (ie: stuffing more insulation into the walls), but the whole right beside it is still leaking. This approach can result in throwing money away on something that has no practical effect on energy use. If we want to achieve real energy savings AND minimize costs, we should consider the impact of these thermal bridging from transitional components in our analysis.